Lately I've been transforming a float based algorithm to integers in order to make it bit-exact. Preserving the precision as best as possible was way more challenging than I initially thought, which forced me to go deep down the rabbit hole. During the process I realized I had many wrong assumptions about integer divisions, and also discovered some remarkably useful mathematical properties.

This story is about a journey into figuring out equivalent functions to

round(a/b), floor(a/b) and ceil(a/b) with a and b integers, while

staying in the integer domain (no intermediate float transformation allowed).

Note

For the sake of conciseness (and to make a bridge with the mathematics

world), floor(x) and ceil(x) will sometimes respectively be written

⌊x⌋ and ⌈x⌉.

Clarifying the mission

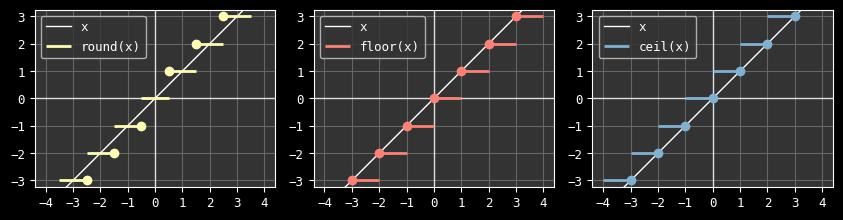

Better than explained with words, here is how the functions we're looking for behave with a real as input:

The dots indicate on which lines the stitching applies; for example round(½)

is 1, not 0.

Language specificities (important!)

Here are the corresponding prototypes, in C:

int div_round(int a, int b); // round(a/b)

int div_floor(int a, int b); // floor(a/b)

int div_ceil(int a, int b); // ceil(a/b)

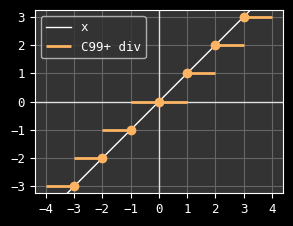

We're going to work in C99 (or more recent), and this is actually the first warning I have here. If you're working with a different language, you must absolutely look into how its integer division works. In C, the integer division is toward zero, for both positive and negative integers, and only defined as such starting C99 (it is implementation defined before that). Be mindful about it if your codebase is in C89 or C90.

This means that in C:

printf("%d %d %d\n", 10/30, 15/30, 20/30);

printf("%d %d %d\n", -10/30, -15/30, -20/30);

We get:

0 0 0

0 0 0

This is typically different in Python:

>>> 10//30, 15//30, 20//30

(0, 0, 0)

>>> -10//30, -15//30, -20//30

(-1, -1, -1)

In Python 2 and 3, the integer division is toward -∞, which means it is

directly equivalent to how the floor() function behaves.

In C, the integer division is equivalent to floor() only for positive

numbers, otherwise it behaves the same as ceil(). This is the division

behavior we will assume in this article:

And again, I can't stress that enough: make sure you understand how the integer division of your language works.

Similarly, you may have noticed we picked the round function as defined by

POSIX, meaning rounding half away from 0. Again, in Python a different method

was selected:

>>> [round(x) for x in (0.5, 1.5, 2.5, 3.5, 4.5, 5.5, 6.5)]

[0, 2, 2, 4, 4, 6, 6]

Python is following the round toward even choice rule. This is not what we are implementing here (Edit: a partial implementation is provided at the end though). There are many ways of rounding, so make sure you've clarified what method your language picked.

Ceiling and flooring

The integer division is symmetrical around 0 but ceil and floor aren't,

so we need a way get the sign in order to branch in one direction or another.

If a and b have the same sign, then a/b is positive, otherwise it's

negative. This is well expressed with a xor operator, so we will be using the

sign of (a^b) (where ^ is a xor operator). Of course we only need to

xor the sign bit so we could instead use (a<0)^(b<0) but it is a bit more

complex.

Edit: note that (a^b) is not > 0 when a == b. Also, as pointed out

on lobste.rs it's likely to rely on unspecified /

implementation-defined behavior (hopefully not undefined behavior). We could

use the safer (a<0)^(b<0) form which only generates an extra shift

instruction on x86.

Looking at the graphics, we observe the following symmetries:

floor(x):- For positive

x, the C division works the same - For negative

x, the C division is one step too high (with the exception of the stitching point)

- For positive

ceil(x)- For negative

x, the C division works the same - For positive

x, the C division is one step too low (with the exception of the stitching point)

- For negative

We can translate these observations into code using a modulo trick (which purpose is to not offset the stitching point when the division is round):

int div_floor(int a, int b) { return a/b - (a%b!=0 && (a^b)<0); }

int div_ceil(int a, int b) { return a/b + (a%b!=0 && (a^b)>0); }

One may wonder about the double division (a/b and a%b), but fortunately CPU

architectures usually offer a division instruction that computes both at once

so this is not as expensive as it would seem in the first place.

Now you also have an alternative without the modulo, but it generates less

effective code (at least here on x86-64 with a modern CPU according to my

benchmarks):

int div_floor(int a, int b) { return (a^b)<0 && a ? (1-abs(a))/abs(b)-1 : a/b; }

int div_ceil(int a, int b) { return (a^b)>0 && a ? (abs(a)-1)/abs(b)+1 : a/b; }

Edit: note that these versions suffer from undefined behavior in case of

abs(INT_MIN) as pointed out by nortti in previous comment about xor.

I have no hard proof to provide for these right now, so this is left as an exercise to the reader, but some tools can be found in Concrete Mathematics (2nd ed) by Ronald L. Graham, Donald E. Knuth and Oren Patashnik. In particular:

- the reflection properties:

⌊-x⌋ = -⌈x⌉and⌈-x⌉ = -⌊x⌋ ⌈n/m⌉ = ⌊(n-1)/m⌋+1and⌊n/m⌋ = ⌈(n+1)/m⌉-1

Rounding

The round() function is the most useful one when trying to approximate floats

operations with integers (typically what I was looking for initially:

converting an algorithm into a bit-exact one).

We are going to study the positive ones only at first, and try to define it

according to the integer C division (just like we did for floor and ceil).

Since we are on the positive side, the division is equivalent to a floor(),

which simplifies a bunch of things.

I initially used a round function defined as round(a,b) = (a+b/2)/b and

thought to myself "if we are improving the accuracy of the division by b

using a b/2 offset, why shouldn't we also improve the accuracy of b/2 by

doing (b+1)/2 instead?" Very proud of my deep insight I went on with this,

until I realized it was causing more off by ones (with a bias always in the

same direction). So don't do that, it's wrong, we will instead try to find

the appropriate formula.

Looking at the round function we can make the observation that it's pretty

much the floor() function with the x offset by ½: round(x) = floor(x+½)

So we have:

round(a/b) = ⌊a/b + ½⌋

= ⌊(2a+b)/(2b)⌋

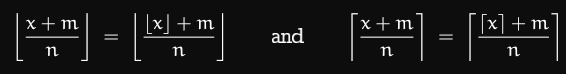

We could stop right here but this suffers from overflow limitations if translated into C. We are lucky though, because we're about to discover the most mind blowing property of integers division:

You may not immediately realize how insane and great this is, so let me

elaborate: it basically means N successive truncating divisions can be merged

into one without loss of precision (and the other way around).

Here is a concrete example:

>>> n = 5647817612937

>>> d = 712

>>> n//d//d//d == n//(d*d*d)

True

That's great but how does that help us? Well, we can do this now:

round(a/b) = ⌊a/b + ½⌋

= ⌊(2a+b)/(2b)⌋

= ⌊⌊(2a+b)/2⌋/b⌋ <--- applying the nested division property to split in 2 floor expressions

= ⌊⌊a+b/2⌋/b⌋

= ⌊(a+⌊b/2⌋)/b⌋

How cute is that, we're back to the original formula I was using: round(a,b) = (a+b/2)/b (because again the C division is equivalent to floor() for

positive values).

Now how about the negative version, that is when a/b < 0? We can make the

similar observation that for a negative x, round(x) = ceil(x-½), so we

have:

round(a/b) = ⌈a/b - ½⌉

= ⌈(2a-b)/(2b)⌉

= ⌈⌈(2a-b)/2⌉/b⌉

= ⌈⌈a-b/2⌉/b⌉

= ⌈(a-⌈b/2⌉)/b⌉

And since a/b is negative, the C division is equivalent to ceil(). So in

the end we simply have:

int div_round(int a, int b) { return (a^b)<0 ? (a-b/2)/b : (a+b/2)/b; }

This is the generic version, but of course in many cases we can (and probably should) simplify the expression appropriately.

Let's say for example we want to remap an u16 to an u8:

remap(x,0,0xff,0,0xffff) = x*0xff/0xffff = x/257. The appropriate way to

round this division is simply: (x+257/2)/257, or just: (x+128)/257.

Edit: it was pointed out several times on HackerNews that

this function still suffers from overflows. Though, it remains robuster than

the previous version with ×2.

Bonus: partial round to even choice rounding

Equivalent to lrintf, this function provided by Antonio on

Mastodon can be used:

static int div_lrint(int a, int b)

{

const int d = a/b;

const int m = a%b;

return m < b/2 + (b&1) ? d : m > b/2 ? d + 1 : (d + 1) & ~1;

}

Warning

This only works with positive values.

Verification

Since you should definitely not trust my math nor my understanding of computers, here is a test code to demonstrate the exactitude of the formulas:

#include <stdio.h>

#include <math.h>

static int div_floor(int a, int b) { return a/b - (a%b!=0 && (a^b)<0); }

static int div_ceil(int a, int b) { return a/b + (a%b!=0 && (a^b)>0); }

static int div_round(int a, int b) { return (a^b)<0 ? (a-b/2)/b : (a+b/2)/b; }

#define N 3000

int main()

{

for (int a = -N; a <= N; a++) {

for (int b = -N; b <= N; b++) {

if (!b)

continue;

const float f = a / (float)b;

const int ef = (int)floorf(f);

const int er = (int)roundf(f);

const int ec = (int)ceilf(f);

const int of = div_floor(a, b);

const int or = div_round(a, b);

const int oc = div_ceil(a, b);

const int df = ef != of;

const int dr = er != or;

const int dc = ec != oc;

if (df || dr || dc) {

fprintf(stderr, "%d/%d=%g%s\n", a, b, f, (a ^ b) < 0 ? " (diff sign)" : "");

if (df) fprintf(stderr, "floor: %d ≠ %d\n", of, ef);

if (dr) fprintf(stderr, "round: %d ≠ %d\n", or, er);

if (dc) fprintf(stderr, "ceil: %d ≠ %d\n", oc, ec);

}

}

}

return 0;

}

Conclusion

These trivial code snippets have proven to be extremely useful to me so far, and I have the hope that it will benefit others as well. I spent an unreasonable amount of time on this issue, and given the amount of mistakes (or at the very least non optimal code) I've observed in the wild, I'm most certainly not the only one being confused about all of this.